Dat Netanyahu’s Corridor het Chinese Belt & Road-initiatief kan verslaan, lijkt uitgesloten, maar Israël en de VS zijn er wel in geslaagd de Europese gasmarkt te veroveren.

In de Gazastrook – en minder omvangrijk ook op de Westelijke Jordaanoever – voltrekt zich een ware genocide. De bommenregen is ongezien hevig. Niet enkel verboden fosforbommen zouden tegen Palestijnse burgers worden ingezet, maar ook bommen van een niet eerder gezien kaliber. Terwijl een eerste fase van het grondoffensief zou zijn ingezet, zendt de Amerikaanse nieuwszender CNN een interview uit waarin wordt aangedrongen op ondersteuning door Amerikaanse Navy SEALs. Extremistische neoconservatieven dromen van een escalatie naar een Amerikaans-Israëlische oorlog tegen Iran. Is het tegen die achtergrond opportuun om ons te buigen over de geopolitieke motieven van de oorlog tegen Palestina? In afwachting van meer nieuws over de oorlog wagen we het erop.

Netanyahu’s Corridor

Boven ons artikel ‘Netanyahu’s dilemma: aftreden of doorgaan voor Nakba 2.0‘ stond een videoclip waarin de Israëlische premier Benjamin Netanyahu de VN zijn versie presenteerde van een nieuw Midden-Oosten. In de analyse focusten we op Netanyahu’s bedreiging van Iran met kernwapens en het ontbreken van elke verwijzing naar Palestina. We haalden de Abraham-akkoorden aan en stelden dat zo’n akkoord met Saoedi-Arabië niet in het verschiet ligt. We bestempelden de Israëlische oorlog tegen Gaza als genocide en stelden dat de VS een door China bemiddeld akkoord tussen Israël en Palestina als een geopolitieke bedreiging zou zien. Maar we werkten Netanyahu’s “nieuwe Corridor van vrede en welvaart die Azië, via de VAE, Saoedi-Arabië, Jordanië en Israël, met Europa verbindt” niet uit.

Netanyahu’s Corridor is een plan van de VS om het Chinese Belt & Road-initiatief (BRI), het investeringsproject in infrastructuur op de route naar Europa, te ondergraven.

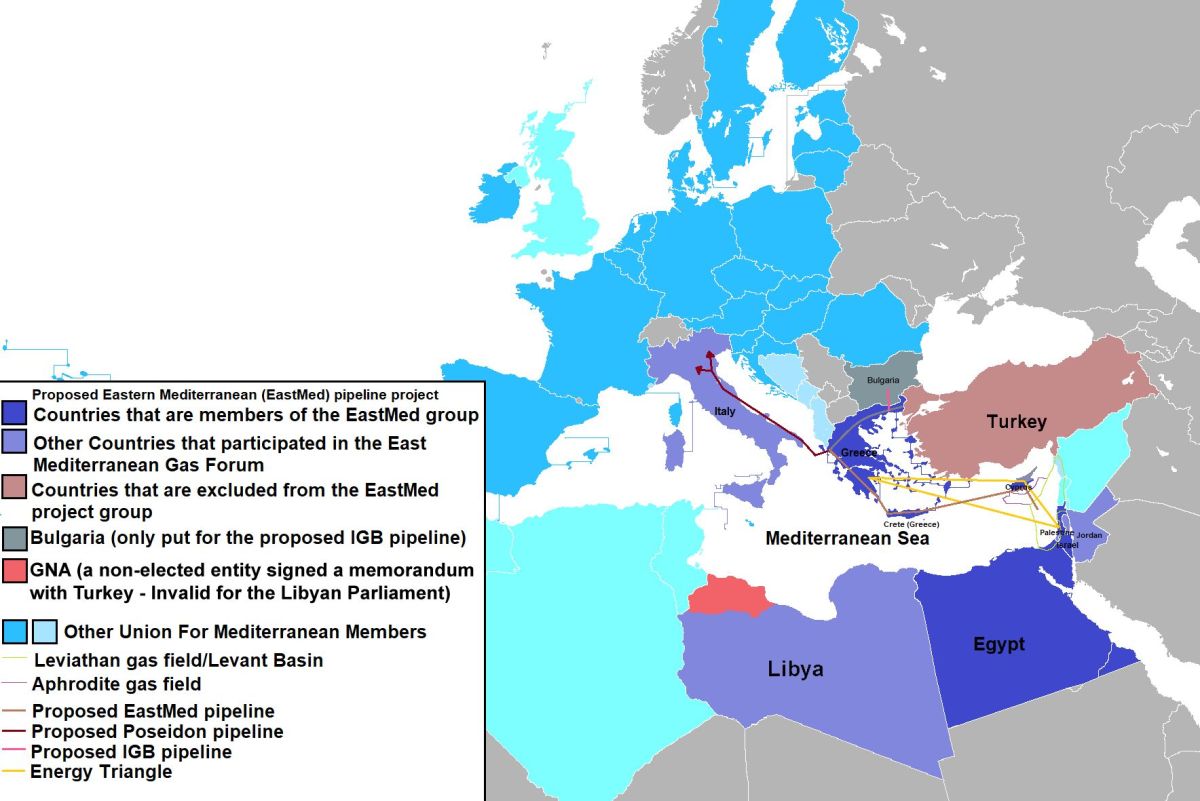

Dat laatste aspect verdient een afzonderlijke analyse. Netanyahu’s Corridor is een plan van de VS om het Chinese Belt & Road-initiatief (BRI), het investeringsproject in infrastructuur op de route naar Europa, te ondergraven. BRI is een project dat een enorme stimulans kan geven aan de wereldeconomie. Het neemt steeds vastere vorm aan. Recent tekenden Iran en Irak het Shalamcheh-Basra spoorwegproject dat Iran uiteindelijk moet verbinden met Europa. Zes maanden na de door China bemiddelde verzoening tussen Iran en Saoedi-Arabië, tekenden de Chinese leider Xi Jinping en de Syrische president Bashar al-Assad een strategisch partnerschap. Dat maakt aansluiting van BRI op de Syrische havenstad Latakia aan de Middellandse Zee mogelijk.

De oorlog in Oekraïne en het opblazen van de Nord Stream pijpleidingen heeft Rusland als gasleverancier van Europa al geëlimineerd. Het opblazen van de nucleaire deal met Iran en het hervatten van Amerikaanse en Europese sancties deed hetzelfde met Iran. In juni 2022 tekende de EU een aardgasexportovereenkomst met Israël en Egypte. Daarmee maakt de Unie zich voor gasleveranties in belangrijke mate afhankelijk van Israël. Het Israëlisch gas wordt voor een stuk illegaal gewonnen in de Exclusieve Economische Zone (EEZ) voor de kust van Gaza waar de Staat Palestina juridisch eigenaar van is. De Israëlische haven Haifa gaat de geo-economische strijd aan met Syrische en Libanese havens die Iraans gas zouden kunnen leveren. Een strijd die niet volgens het boekje lijkt te verlopen.

Beiroet

Israël heeft achter de schermen een grote rol gespeeld in de proxy-oorlog in Syrië. De VS heeft bases ingericht in het noordoosten en heeft daarmee de controle op 1/3 van het land en 100% van de Syrische gas- en olievelden. Israël bombardeert met grote regelmaat steden in het land, incl. de havenstad Latakia. En wie herinnert zich niet de apocalyptische explosie in de haven van de Libanese hoofdstad Beiroet? De explosie werd toegeschreven aan de spontane ontploffing van opgeslagen ammoniumnitraat, en door westerse bronnen omschreven als “de grootste niet-nucleaire explosie sinds het einde van de Tweede Wereldoorlog”. Maar was die explosie, die meer dan 200 mensen heeft gedood en een groot deel van de Libanese hoofdstad met de grond heeft gelijkgemaakt, écht niet-nucleair?

Maar was die explosie, die meer dan 200 mensen heeft gedood en een groot deel van de Libanese hoofdstad met de grond heeft gelijkgemaakt, écht niet-nucleair?

De Amerikaanse chemisch ingenieur Bruce Baird heeft de explosie geanalyseerd en zijn bevindingen in een Twitter-draadje vastgelegd. 2750 ton ammoniumnitraat, gestapeld in zakken op de vloer van een pakhuis, blaast geen 43 meter diepe krater in de bodem. Hij citeert uit het legerdocument Explosives and Demolitions van 27 augustus 2008: “Van alle militaire explosieven is ammoniumnitraat het minst delicaat. Een succesvolle ontploffing vergt een ontstekerlading”. Volgens Baird werd de explosie veroorzaakt door een 5+ kT ondergrondse kernbom, in de VS ontwikkeld in de jaren zeventig, om kraters, ontploffingen en grondschokken te maximaliseren en tegelijk de fall-out te minimaliseren. Ruim drie jaar na dato is het opmerkelijk dat een officieel – Libanees of internationaal – onderzoek op zich laat wachten.

LNG-terminals

Hoe het ook zij, Latakia noch Beiroet liggen op koppositie als het gaat om een betrouwbare locatie voor LNG-terminals voor Iraans aardgas bestemd voor Europa. Dat staat Israël toe zich zelfbewust te positioneren als dé oplossing voor de energieproblemen van de EU. In een persbericht van 28 juni 2021 liet Stena Drilling weten een nieuw contract te hebben gesloten met Energean Israel voor de levering van het boorschip ‘Stena IceMAX’. Het schip zal het boorprogramma van Energean voor 2022-2023 in de Middellandse Zee, voor de kust van Israël, ondersteunen. De laatste Israëlische statistieken wijzen op 750 miljard kubieke meter aan bewezen gasreserves. De Palestijnse gasreserves voor de kust van Gaza zijn ooit geraamd op 30-45 miljard kubieke meter. Naar recente gegevens hebben we het raden.

In de aanloop naar de winter kan de oorlog tegen de Palestijnen in Gaza nefaste gevolgen hebben voor de Europese voorziening van LNG.

Er zijn ernstige geschillen tussen Cyprus, Griekenland, Libanon, Palestina en Turkije over het recht op de gasvelden in het oostelijke Middellandse Zeegebied. Palestina zal zijn gasreserves maar kunnen aanboren zodra er een tweestatenoplossing is die voorziet in een volledig soevereine staat Palestina. Onder het mom van veiligheidsbekommernissen blijft Israël de controle op het Palestijnse gasveld aan zich toe-eigenen. Het geschil tussen Libanon en Israël lijkt het meest explosief. Hezbollah’s secretaris-generaal Hasan Nasrallah heeft al gedreigd Israëlische of buitenlandse boorschepen in betwist maritiem gebied aan te vallen zolang de Libanese regering nog onderhandelt. In de aanloop naar de winter kan de oorlog tegen de Palestijnen in Gaza nefaste gevolgen hebben voor de Europese voorziening van LNG.

Rivalen

Door rivalen uit te schakelen zijn Israël en de VS er grosso modo in geslaagd de Europese gasmarkt te veroveren. Israël heeft de ambitie om aan de touwtjes van de Europese gasmarkt te trekken. Blijft de vraag hoe de oorlog eindigt. Israël dacht dat de deal met Saoedi-Arabië voor het oprapen was, maar dat is verleden tijd. De regio zal instabiel blijven zolang de problematiek van de Palestijnen niet is opgelost. Israël denkt door de slachting in Gaza en de aanhoudende aanvallen op Palestijnen op de bezette Westelijke Jordaanoever een Nakba 2.0 tot stand te kunnen brengen: Gazanen én Westbankers naar de Sinaï-woestijn (Egypte). Het laatste nieuws is dat aangeslagen Palestijnen toegang beginnen te vragen tot de Sinaï, en de Egyptische president onder de zwaarste druk wordt gezet om de grens te openen.

We kijken aan tegen een beslissend moment in de recente geschiedenis. Dat het Westen het Chinese Belt & Road-initiatief kan verslaan, lijkt uitgesloten. Als Rusland Damascus van degelijke luchtafweer voorziet, zullen de Israëlische luchtaanvallen op dat land snel tot het verleden behoren en Latakia zijn LNG-terminal voor Iraans gas kunnen bouwen. Als Hamas erin slaagt via de naar Egypte en Jordanië uitlopende tunnels de bevolking te voorzien van minimale voorraden, kan de strijd nog lang voortduren. Als Israël zich zou laten verleiden het grondoffensief maximaal op te voeren, loopt het het risico te worden verslagen. En als Israël toch snel weet af te rekenen met de al-Qassam brigades, dan is het nog maar de vraag of de Arabische straat zich neerlegt bij een Endlösung van het Palestijnse vraagstuk.

Wordt het geopolitieke schaakbord herschikt? De toekomst zal het leren.